Collaboration, Not Control: Governing from the Supermajority

September 4, 2025

By Elizabeth Rosen

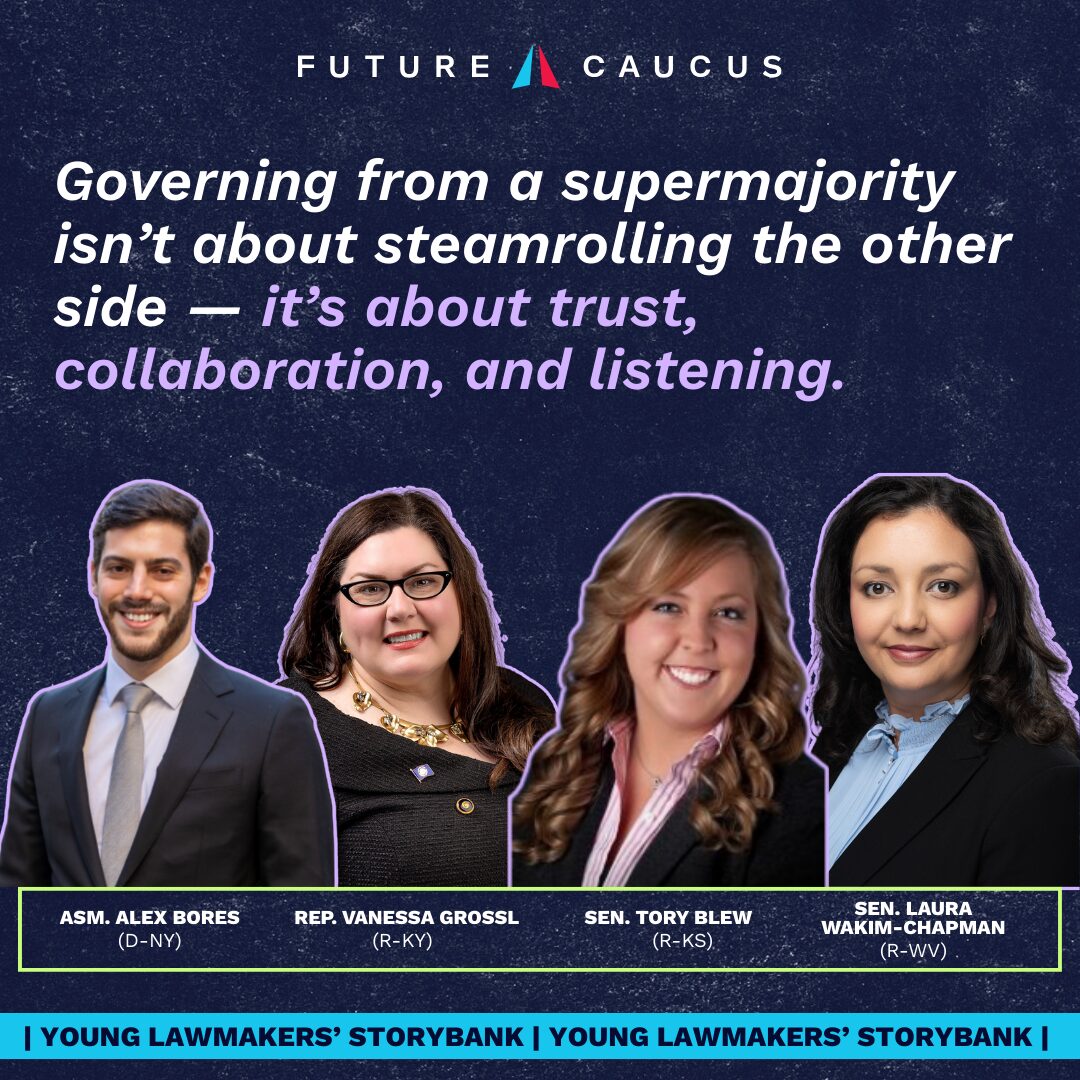

This story is part two of a two-part series exploring what it’s like to govern from the superminority and the supermajority in state legislatures. Even in states where their party holds a commanding majority, Future Caucus members from Alabama, Kansas, Kentucky, New York and West Virginia say governing is still about listening, trust and compromise.

When people picture a statehouse dominated by one party, they might envision policymaking by steamroller, a tyrannical majority governing over the heads of a resigned — or ineffectually belligerent — minority. But members of the Future Caucus network say the reality is more complicated and collaborative than that.

“Most of the things we do are bipartisan, even though we’re a supermajority,” said Rep. Vanessa Grossl, R-Ky. “I always think there’s room to compromise and collaborate and find common ground. I just say ‘yes’ to all the meetings — I love to be surrounded by people who will give me perspective on all the issues.”

That openness runs through the stories of supermajority members in states across the country. In Kansas, Republican state Sen. Tory Blew said she is “excited to show that just because we are in the supermajority doesn’t mean we have to act like we’re in the supermajority, and you do have to work across the aisle.”

Blew challenged her colleagues to ask themselves whether getting everything they wanted from a day of lawmaking truly served the broader public. Those who believed the answer was yes, she argued, were in the wrong line of work. Representing Kansans of every party and affiliation, she said, requires working across the aisle and resisting the temptation to pass legislation that only reflects one side’s priorities.

“I think bipartisanship can improve bills,” said Asm. Alex Bores, D-N.Y. “You need representation from throughout the state. You need ideas from a lot of different perspectives in order to get the best versions of ideas forward.”

Bores recalled introducing a bill to modernize outdated language in court filing requirements, replacing “color of skin” and “sex” with “race” and “perceived gender,” respectively. His first draft drew Republican opposition.

“My first instinct, honestly, was, ‘Ooh, I’m going to love this debate,’” he said. But when he listened more closely, he realized their concern was valid: the phrase “perceived gender” left it unclear whose perception was being recorded.

“That’s a very reasonable response,” Bores admitted. He revised the language, won bipartisan support and ultimately passed a stronger bill. “I could have shoved that bill through in a supermajority, but actually listening to my colleagues got to a bill that was better for everyone.”

Members of supermajorities also have to navigate divides that don’t fall neatly along party lines. Blew noted that in Kansas, rural voices can sometimes feel drowned out, even in a Republican-controlled legislature.

“There’s the Republican-Democrat label side of it, but there’s also the urban-rural side,” she explained. “Kansas is primarily rural, but if you take where I live in the middle of the state and go west, there are only 12 representatives out of 125. So on some issues, I’m in the superminority of legislation that mostly benefits urban areas. In the Kansas Future Caucus, we have Republicans, Democrats, rural, suburban and urban voices, and I think those conversations are really important to have.”

For Sen. Laura Wakim-Chapman, R-W.Va., reaching out across the aisle is both practical and principled.

“I make sure to reach across the aisle on anything I’m working on,” she said. “I respect the people in the minority and their viewpoints — everybody was elected, and everybody should have a say. I’ve worked with Kayla Young on the House side to get my bills passed, because with bipartisan support, there’s a better chance a bill will succeed, even in a supermajority.”

“For example,” Wakim-Chapman continued, “Delegate Young and I championed a bill to protect children in institutional settings, which was inspired by Paris Hilton’s moving remarks at a Future Caucus event about her own childhood abuse, and her advocacy for children in similar situations today.”

For supermajority lawmakers like Grossl, Blew, Bores and Wakim-Chapman, bipartisanship isn’t just about smoothing egos or keeping up appearances. It’s about producing legislation that reflects more voices and endures over time.

“You can always find something that you can work together on, even if you’re completely opposed on so many other issues,” Grossl said.

And despite the perception of gridlock, most state-level policymaking is remarkably cooperative.

“It’s not as bad as you think it is,” Bores said. “We pass probably 800 bills a year in New York, and 600 of them are things we all agree on and go on consent. So even though your newsfeed may be really contentious, there’s great work that we do across the aisle every single day.”

Blew added that in Kansas, “90% to 95% of bills we passed are 125 to zero [in the House], and 40 to zero or 39 to one [in the Senate].”

Occasionally, those cross-partisan ties are what push a bill over the finish line. Rep. Parker Moore, R-Ala., noted that his curbside alcohol legislation needed Democratic support to pass, while Asm. Brian Cunningham, D-N.Y., pointed out that even in a Democratic supermajority, “you can’t leave behind the 6 million Republicans who also live in our state.”

Ultimately, members in the supermajority share the same lesson as their colleagues in the superminority: governing well requires relationships, trust and a willingness to listen. As Cunningham put it, “We’re all in this together, and we’re all trying to make our cities, our states and our country a little better.”

Join 1,900+ BIPARTISAN LEADERS NATIONWIDE

Be a part of a network of lawmakers committed to governing effectively, passing more representative public policy, and increasing public trust in democracy.